It's been a while since I've written for The City Paper, and I'd like to connect with them. It's okay if I write about my brain tumor, since I hear about this all the time from Charleston and all over the country. But I need to write something that's not exactly what I've written before. For instance, Chris at The City Paper said, "And it’s cool to mention your ongoing trouble with words, but do so sparingly bc we’ve touched on that several times." I see what he's saying--I do think about communication all the time, but it's not all that exciting for any of you all.

So: any ideas? That's truly why I'm writing this. Give me some thoughts. I might be inspired and will write an article for the paper.

Monday, December 21, 2015

Wednesday, December 16, 2015

Oh, I hate the IV infusion

Let me start with the good things, which are significant and important:

- In the "port place" at MUSC's Hollings Cancer Center, nurses kindly fill me up with all kinds of useful medicine. They're really nice people, consistently, and I know they are doing everything they can to help me.

- The chemo is working, as I learned last week when I visited my team at the Duke University hospital.

- I only have to have the IV infusion every other week.

- I like the socks that my mom got me.

|

| Lovely socks, not too cold for Charleston. |

Now, onto what I'm here to write about. How I hate it here in the hospital. I've been here once every other week for several months, and it's gotten worse and worse in my feelings about this experience. It's not that I'm really experiencing awful panic attacks or severe pain--not at all. But here are things that make me anxious, angry, out of control.

- This places smell just like the places I've encountered elsewhere in this hospital. More than anything it smells like baby Maybelle when she was in the NICU, also at MUSC. She was born, and then she was in the NICU for a full week. A full week. You'd have to wash your hands before you entered the room, so every time--multiple times every day--I'd have to scrub my hands with the soap that smells exactly like the smell here. It makes my heart hurt every time I smell that soap. I hate it. I hate Maybelle having to be there in her first seven days of life, only because they were concerned that she had Down syndrome. There wasn't anything other than that. After we discovered her fantastic pediatrician, he said that what she needed was time outside every day.

- Damn it.

- It can take forever for the medicine to be delivered. Once in the last month, it took two hours for them to even bring the medicine for the IV infusion. I sat in the chair, plugged into everything, but doing nothing. For an extra two hours.

- That sucks.

- I'm sitting here right now, getting some prophylactic medication for diarrhea/nausea/agony -- that's a good thing, actually, not one that I hate -- and the nurse just discovered that it's actually going to take longer than she thought, because the doctor wanted to see how much I weigh. I was 139 pounds a few weeks ago. Now I'm back at 149--which is very good, because it means I'm moving back to the normal weight of my body (155 since I was in grad school). She discovered that we're going to have to wait some more, because my weight change required a revision in my dosage.

- What the hell!

- Now I'm home. I'm exhausted--falling asleep--but I wish I could take a shower and throw all my clothes in the laundry. I'm too tired for that right now, but the smell of my clothing is hard to take when the clothing is so near to me. The smell is the first item on my list of things I hate about IV infusion.

- Breaking my heart sometimes.

Thursday, December 10, 2015

No longer have to wait

|

It's excellent news. My Three People Dream Team at Duke Cancer Center were satisfied that this time through, the chemo is working.

I'm sorry that I don't have more to say. After a full day of that sort of intensity, I'm completely exhausted. I'm going to finish writing this message and then go to bed.

Wait

I got up at 5am this morning. Brian and I were on the road at 6:10am. I had an MRI at 12:15pm.

And now here we are. Brian and I are at Duke's Cancer Center, just outside the neuro-oncologists' office where my three medical folks will talk with me. It's 2:35pm, and we're early. We've been early every step of the day. Being early makes no difference--it could be an hour or more before we find out what Sharon, Gordana, and Elaine have learned in the MRI.

Will they see it exactly the same? Will they see it shrinking? Growing? This is a moment when they have to assess this tissue carefully, spending minutes, hours, to see what the MRI is saying. It's not easy, and obviously they have to take it very, very seriously.

Years ago, my neuro-oncologist was great, although I'm not sure I agree with everything he did. For example, I had an MRI before the holidays. Lights were up on trees on Rutledge Ave. We had a Christmas tree in our house. Maybelle and I were soon going to go home and be with my parents for a couple of weeks. Jim called (I always call professional doctors by their first names, and they do the same--works well). My body was instantly flushed with adrenaline.

"It's looking good," Jim told me. "Nothing to worry about. Merry Christmas!"

Relief washed through my body. Here we were, Christmas. Of course, it was the 2011 holidays--shit was all over the place in the holiday challenges--but they weren't about the brain tumor.

Shortly after the holidays were over, Jim called. "We're seeing a little growth in your tumor," he said. The tumor had begun growing before the holidays, but he didn't want me to have to deal with that fear and depression during the holiday season.

Kind, I know. But not what I want. This is my body. I am central to the decision-making here. The medical team will provide information, then we'll talk to find out what options are available, what they mean to me. Every time I'm interested in my death and whether it's time for me to begin making those plans. I feel like a full, blessed, loved, supported person when I'm allowed to be an adult in days like today.

The day before my birthday.

We're still waiting in the lobby. I'll let you know what I find out.

And now here we are. Brian and I are at Duke's Cancer Center, just outside the neuro-oncologists' office where my three medical folks will talk with me. It's 2:35pm, and we're early. We've been early every step of the day. Being early makes no difference--it could be an hour or more before we find out what Sharon, Gordana, and Elaine have learned in the MRI.

Will they see it exactly the same? Will they see it shrinking? Growing? This is a moment when they have to assess this tissue carefully, spending minutes, hours, to see what the MRI is saying. It's not easy, and obviously they have to take it very, very seriously.

Years ago, my neuro-oncologist was great, although I'm not sure I agree with everything he did. For example, I had an MRI before the holidays. Lights were up on trees on Rutledge Ave. We had a Christmas tree in our house. Maybelle and I were soon going to go home and be with my parents for a couple of weeks. Jim called (I always call professional doctors by their first names, and they do the same--works well). My body was instantly flushed with adrenaline.

"It's looking good," Jim told me. "Nothing to worry about. Merry Christmas!"

Relief washed through my body. Here we were, Christmas. Of course, it was the 2011 holidays--shit was all over the place in the holiday challenges--but they weren't about the brain tumor.

Shortly after the holidays were over, Jim called. "We're seeing a little growth in your tumor," he said. The tumor had begun growing before the holidays, but he didn't want me to have to deal with that fear and depression during the holiday season.

Kind, I know. But not what I want. This is my body. I am central to the decision-making here. The medical team will provide information, then we'll talk to find out what options are available, what they mean to me. Every time I'm interested in my death and whether it's time for me to begin making those plans. I feel like a full, blessed, loved, supported person when I'm allowed to be an adult in days like today.

The day before my birthday.

We're still waiting in the lobby. I'll let you know what I find out.

Tuesday, December 1, 2015

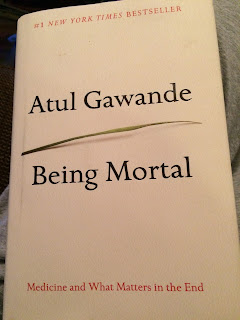

Being Mortal

The author, Atul Gawande, is a surgeon--both, I guess, an author and a surgeon at the same time. He brings those two things together as he tells stories of patients. And more than patients: he's talked with the individuals who appear here. He's not performing as some sort of withdrawn medical expert. Instead, he gives details about people's lives, and his own changes become one of the key elements in the book.

Look at some of what I've marked as I've gone through the book:

"People with incurable cancers, for instance, can do remarkably well for a long time after diagnosis. They undergo treatment. Symptoms come under control. They resume regular life. They don't feel sick. But the disease, while slowed, continues progressing, like a night brigade taking out perimeter defenses" (26).Remarkably well. But. It's remarkable! Not what we expected! A surprise! But. Night brigade. I don't like any of this. The framing is terrible in terms of my own writing, thinking, experiencing, feeling. I feel that I'm losing a battle that I'm not even fighting. I get to frame this, not go by the familiar stories.

He discusses Stephen Jay Gould:

"'It has become, in my view, a bit too trendy to regard the acceptance of death as something tantamount to intrinsic dignity," [Gould] wrote in his 1985 essay. "I prefer the more martial view that death is the ultimate enemy--and I find nothing reproachable in those who rage mightily against the dying of the light'" (171).Here's another one I find offensive. Well, maybe not offensive. Maybe just something that scrapes against me. He himself is allowed to fight, to have an enemy, to "rage mightily" against the death. But I don't want to be in that place. That rage would give me a kind of energy that grows, and it's not the energy I want. I want to put my energy elsewhere, in a lot of the ways I've blogged about.

"With this new way, in which we together try to figure out how to face mortality and preserve the fiber of a meaningful life, with its loyalties and individuality, we are plodding novices. We are going through a societal learning curve, one person at a time. And that would include me, whether as a doctor or as simply a human being" (193).Whew. Yes. This is the kind of statement that makes me step away from the book. How to face mortality and preserve the fiber of a meaningful life. So often he examines how people die--in horrible scenarios in hospitals, and in much better scenarios when they're being carried to (through?) their death with guidance through hospice. I remember Nana, my grandmother, went through hospice as she died. I remember my aunt and dad and I (and other people--surely others of us were there?) sitting with Subway sandwiches. My aunt kept one hand on her mother's, as Nana lay there, eyes closed. Her breathing was slower and slower, until she stopped breathing.

It's a respectful, kind, supportive process. I read the book and think of Nana, and I think of myself. I want hospice like Nana. I want beautiful songs and cremation like Frank.

And I go get a cup of tea. I turn on Netflix for some ridiculous Christmas movie.

Sometimes I didn't have to put the book down, but I'd follow my dad's lead when it comes to frightening movies: when it's too scary, then you step back and examine the process. "Look at the way they built that shark. You can't even believe that it's a shark when it does that" or "Alien is great because we can see all the slime--they're trying to make it really frightening."

So: Being Mortal is difficult for me to read because there are people dying, people with cancer, people suffering. So in those moments, I look at the process: Gawande includes his own narrative with the frightening or overwhelming information. Look how he slides from others' stories and his own. How does he include the narratives of others? One of my comments in the margins: "Story, info, story via info." What he includes and what it does--how does he do this? Would I like to see him write more about his own narrative?

"Well-being is about the reasons one wishes to be alive. Those reasons matter not just at the end of life, or when debility comes, but all along the way. Whenever serious sickness or injury strikes and your body or mind breaks down, the vital questions are the same: What is your understanding of the situation and its potential outcomes? What are your fears and what are your hopes? What are the trade-offs you are willing to make and not willing to make? And what is the course of action that best serves this understanding?" (259).Motherfuck. This is a way to reject these questions, but Cheryl Strayer would say, Write like a motherfucker. Can't dismiss the life I'm living. So I sit here with the questions, and I let those questions float around in my mind, my body, the places I sit, the feelings of the holiday as it emerges throughout the neighborhood. Smell. Taste. Breath.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)